Thanksgiving and the Tension of American Memory: A Reflection

Thanksgiving invites us each year to pause, give thanks, and reflect—but it also invites us to rise above the myths we’ve inherited. Like many American holidays, Thanksgiving carries a story full of contrasts: celebration woven with suffering, gratitude intertwined with tragedy.

The First Thanksgiving: 1621

“The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth” (1914) by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe

In 1621, the Wampanoag people and the Pilgrims of Plymouth shared a harvest feast. It included wild game, fish, corn, vegetables, and dried fruits—far from the modern meal we imagine.

What we often forget is that this moment was only possible because of the extraordinary generosity of the Wampanoag, who taught the Pilgrims how to survive.

The Pilgrims: Religious Refugees

The Pilgrims were English religious separatists fleeing persecution, seeking the freedom to practice their Calvinist-influenced faith without belonging to the State Church. After years in exile in Holland, they found investors, sailed to North America in 1620 and founded Plymouth Colony.

The Wampanoag: Sustainers of the Colony

Before European contact, the Wampanoag numbered around 40,000 across 57 villages. But between 1616–1619, during the Great Dying, diseases brought by earlier European visitors devastated entire communities. By the time the Mayflower arrived, only about 2,000 Wampanoag remained.

In March 1621, Samoset, speaking English, welcomed the Pilgrims and introduced them to his Chief, Ousamequin (Massasoit), who forged a peace treaty and alliance. The Wampanoag taught the Pilgrims to fish, hunt, and farm—literally saving them from collapse.

The 1621 feast we call “The First Thanksgiving” happened because the Wampanoag ensured the colony survived.

The Tragic Turn: King Philip’s War

After Ousamequin’s death, his son Metacom (known to the English as King Philip) watched colonists violate treaties and seize Wampanoag land.

In 1675, tensions erupted into King Philip’s War, a 14-month conflict still considered the deadliest per capita in U.S. history.

- Two-thirds of the Wampanoag alliance died

- One-third of the colonial coalition died

- Wampanoag villages were burned

- Wampanoag women and children were killed or enslaved

Metacom was eventually captured and killed; his head was displayed in Plymouth for 20 years. The Wampanoag were nearly destroyed.

The Fate of America’s Indigenous Peoples

At first contact, Indigenous peoples across North America numbered roughly 20 million. By 1900, the U.S. Census counted only about 250,000.

For many Native communities, Thanksgiving is now a National Day of Mourning, a nationally sanctioned tradition 50 years old—honoring the resilience of their ancestors and the grief of their history.

This is the tension of American memory: moments of cooperation overshadowed by conquest and loss.

The Modern Holiday: A Call for Unity

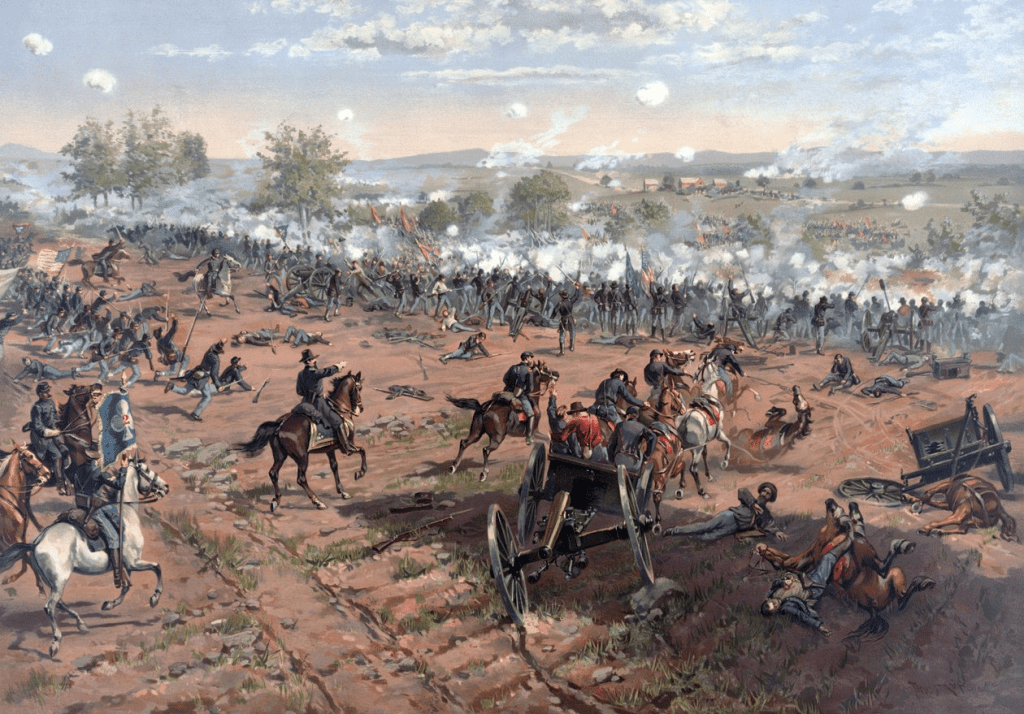

“The Battle of Gettysburg” (1884) by Thure de Thulstrup

Our modern Thanksgiving grew from the vision of Sarah Josepha Hale, who starting in 1846, spent 17 years campaigning for a national holiday to unite a increasingly divided country.

In 1863—just months after Gettysburg—Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgiving a national holiday. His proclamation, written by William Seward, called the nation to gratitude, repentance, unity and healing.

In a nation torn apart, Lincoln hoped Thanksgiving might bind Americans together.

So How Should We Hold This Day?

Thanksgiving is:

- A day of gratitude for abundance and blessing

- A day of lament for the suffering and displacement of Indigenous peoples

- A day of reflection on what kind of nation we’ve been, and are becoming

- A day to remember Lincoln’s hope that we might live up to the name The United States of America

Holding gratitude, grief and hope together is not unpatriotic—it is honest, mature, and necessary for healing.

A Better Word…

If there is a word that can hold all these tensions, it is shalom. Shalom (שָׁלוֹם) is often translated as “peace,” but it means far more: wholeness, harmony, right relationship, justice, completeness, and flourishing—with God, with others, with creation, and within ourselves.

Shalom can also describe a nation, and it stands in contrast to another word—empire. History is filled with empires. In the Ancient Near East: Egypt, Babylon, Rome were dominant empires.

Empires seek greatness; Shalom seeks wholeness.

Empires hoard blessing; Shalom shares it.

Empires forget their wounds; Shalom heals them.

And the one enduring prayer of people living under Empire throughout history is: God rescue us from oppression.

A true Thanksgiving—one honest about both joy and sorrow, abundance and injustice—should also move us closer to shalom, both personally and as a nation.

Shalom to all this season.