Extraordinary Measures

This piece did not begin as an abstract inquiry.

It began with a convergence of events—and a surge of emotion that would not settle.

It all started when ICE operations expanded across Minnesota, producing fear among non-citizens.

Anger when a fellow SEM student from Africa was detained and informed he was being deported. What had felt distant became personal.

Federal agents soon appeared in public spaces using military-style weapons and tactics—not only against undocumented immigrants, but against citizens as well. The use of force by civil authorities against civilians raised immediate concern.

That concern hardened into grief and outrage on January 7, 2026, when U.S. citizen Renee Nicole Good was fatally shot by an ICE agent during an enforcement operation. Federal officials claimed self-defense; eyewitness accounts and video evidence raised serious disputes. No federal civil-rights investigation followed.

Days later, a white supremacist and January 6 rioter—previously convicted of assaulting police—arrived in Minneapolis to support federal immigration enforcement and oppose Somali immigrants. Fewer than ten supporters joined him before he was driven out by counter-protesters. The anger was not about speech, but about impunity: a man who attacked police with a baseball bat now freely mobilizing. seemingly under federal protection.

Soon after, the Department of Justice announced investigations into Minnesota officials and Renee Good’s family for alleged obstruction of immigration enforcement. No parallel investigation was announced into the agent who killed her.

Then came threats of escalation—thousands more ICE agents, and warnings that military paratroopers could be deployed to “restore order.”

Anger dominated—amplified by rhetoric portraying these actions as crime control and framing “sanctuary cities” as magnets for criminals and terrorists. Fear was being cultivated to justify extraordinary force by civil authorities.

I initially wanted to write something scathing. But hyperbole obscures more than it clarifies.

So I slowed down.

What follows is not outrage.

It is a structural argument.

How Emergency Logic Becomes Normal Governance

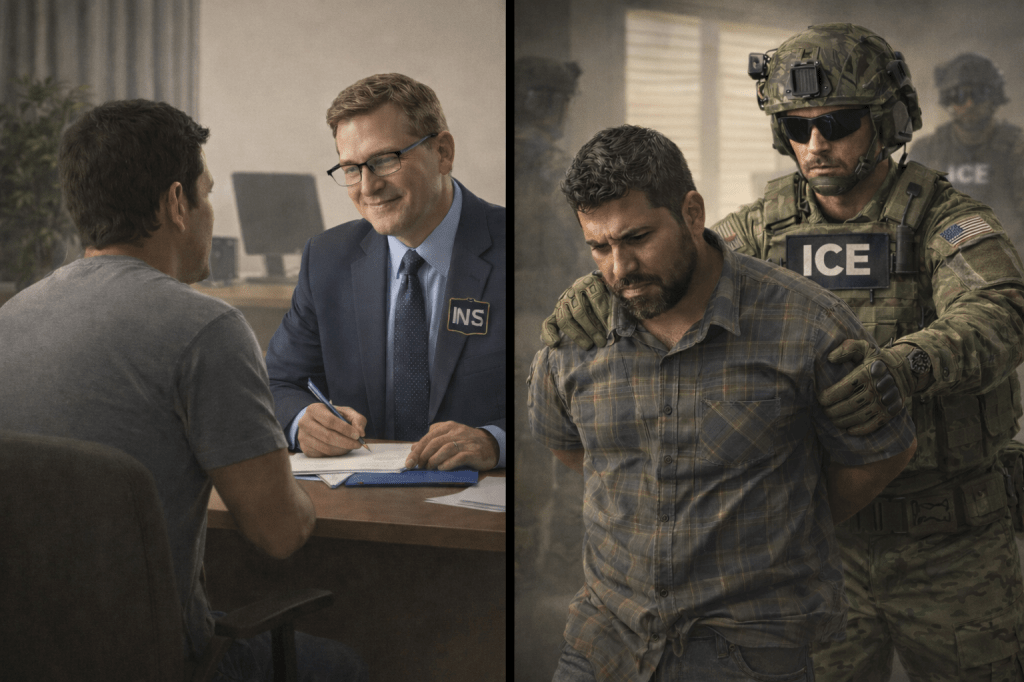

ICE was created after 9/11 under a familiar rationale: extraordinary threats require extraordinary measures. Formed from the former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), it was presented as a narrow security reform—intended to correct immigration enforcement failures and prevent terrorism.

That framing mattered. A specific threat—foreign-born terrorism—was gradually expanded to encompass all immigrants and then elevated to an existential danger, making ordinary legal limits appear reckless rather than protective. Over time, the mission expanded far beyond its original scope.

Today, ICE employs more than 22,000 officers and agents and—following recent congressional action—has become the most heavily funded federal enforcement agency in U.S. history. Under the 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act, Congress authorized roughly $170 billion in new immigration and border enforcement funding through 2029, with about $75 billion directed specifically to ICE: nearly $30 billion for personnel and operations and $45 billion to expand detention capacity. This places ICE’s funding above the combined annual budgets of the FBI, DEA, Bureau of Prisons, ATF, and U.S. Marshals.

Yet ICE is not a criminal law-enforcement agency. It does not investigate crimes, determine guilt, or prosecute offenses. Its authority derives from civil immigration law, and its agents are legally analogous to IRS or OSHA officials—placing people into civil custody for administrative proceedings rather than making criminal arrests.

Despite this limited mandate, ICE now deploys armed personnel, military-style tactics, and large coordinated operations that resemble policing or paramilitary activity. When concentrated in a single city, ICE can rival or outnumber local police forces—exercising immense coercive power while operating outside the criminal justice system and its constitutional safeguards.

This expansion has coincided with a striking reality: as of late 2025, approximately 74 percent of people in ICE detention had no criminal history, despite repeated claims that enforcement targets “dangerous criminals.”

In practice, ICE’s focus has shifted from rare counterterrorism coordination to routine interior enforcement. Mass detention, deportation, and deterrence are now central functions. Fear was never named as policy—but it emerged predictably from scale, visibility, and discretion.

What began as an emergency response has hardened into a permanent domestic enforcement apparatus—now the largest enforcement agency in the federal government—wielding expansive coercive power while operating outside the limits and safeguards of the criminal justice system. It is a clear illustration of how extraordinary measures, once normalized, become difficult to reverse.

When Civil Authority Uses Criminal Force

ICE, like the IRS and OSHA, is legally a civil administrative agency.

Immigration violations are generally civil matters, and for most of U.S. history immigration enforcement functioned much like other regulatory systems: paperwork-driven, court-based, and focused on determining legal status through civil proceedings. Removal, when it occurred, followed administrative hearings and judicial review rather than arrest and detention-led enforcement.

The system relied primarily on notice, compliance, and oversight, not force. When individuals were suspected of criminal activity—violent crime, organized crime, or national-security offenses—those cases were investigated and prosecuted within the criminal justice system. Immigration authorities played a supporting role, primarily to establish status once criminal proceedings were underway.

For much of the twentieth century, immigration administration under the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was oriented toward processing lawful entry and integration: issuing visas, reuniting families, administering naturalization, and maintaining records. This reflected a broader national policy that understood welcoming immigrants was a normal and beneficial feature of American life.

Enforcement existed, but it remained administrative and judicial in character, bounded by civil process rather than organized around arrest, mass detention, or coercive operations.

After 9/11, immigration enforcement narrowed and hardened. With the creation of ICE, immigration was reframed as a security problem, shifting the focus from legal entry and integration toward detection, detention, and removal. An agency once associated with welcoming newcomers became defined by enforcement and exclusion.

The underlying law did not change. Immigration violations remained civil matters. What changed was the method of enforcement. Immigration authority increasingly came to be exercised through tools borrowed from criminal policing—armed agents, interior arrests, mass detention, and large coordinated deployments—while still operating under civil rules that provide fewer protections.

The result is an agency that enforces civil law through police-style coercion, routinely depriving people of liberty without the safeguards that normally accompany criminal enforcement, making ICE an outlier among administrative agencies.

In practice, this includes tactical operations in homes and workplaces, reliance on administrative rather than judicial warrants, detention used as leverage through prolonged or distant confinement, collaboration with local law enforcement that turns routine encounters into immigration cases, and broad surveillance that draws in observers and bystanders. Measures once justified as exceptional have become institutionalized.

Officially, ICE’s actions remain administrative, not punitive. The agency does not prosecute criminal guilt; when criminal activity is identified, cases are referred to the criminal justice system. In its early years, ICE largely operated within this framework, relying on notice, interviews, hearings, and supervised compliance rather than force.

Today, that distinction is far less visible. For many subjected to ICE enforcement, arrest, detention, confinement, and family separation are the lived experience—functionally punitive outcomes imposed through civil authority.

The issue is not simply the use of force, but where it sits within the legal structure. Traditional criminal policing is constrained by judicial warrants, higher evidentiary standards, guaranteed counsel, time-limited detention, and continuous oversight. ICE operates largely outside these constraints while using similar coercive tools, lowering the friction that normally restrains state power and allowing extraordinary enforcement to become routine.

If extraordinary power no longer requires extraordinary justification, the emergency has already become the system.

What This Structure Produces

— and Why It Reaches Citizens

When emergency authority becomes routine, its effects are predictable—and they spread.

Extraordinary power becomes ordinary.

Tools once justified for crisis quietly become standard practice, no longer needing explanation.

Safeguards erode by bypass, not repeal.Civil process replaces criminal process, and protections over homes, movement, and liberty fall away without formal change.

Fear becomes an enforcement tool. Uncertainty, visibility, and disruption generate community-wide deterrence, even without explicit intent.

Over time, civic trust collapses. Courts, workplaces, and public spaces turn into enforcement zones.

Citizens feel the consequences.

When it Reaches Citizens: What This Looks Like

Though officially a civil immigration agency, ICE’s recent operations in Minneapolis have extended into public-order and crowd-control spaces—bringing agents into sustained contact with U.S. citizens as protesters, bystanders and peaceful observers. In multiple demonstrations, ICE agents used tear gas, pepper spray, and other riot-control tactics against crowds that were largely nonviolent.

January 7, 2026 — The Fatal Shooting of Renée Good

On January 7, 2026, 37-year-old U.S. citizen Renée Nicole Good was fatally shot by an ICE agent during a federal enforcement operation in south Minneapolis. Good was trying to drive away in her SUV when the agent she was talking to resorted to violence. Her words: “Hey dude, its okay I’m not mad at you.” His response shooting her four times as she moved forward, followed by saying “Fucking bitch”. Federal officials described the shooting as self-defense; however, eyewitness accounts, video evidence, and reporting have raised serious disputes about that narrative. The Department of Justice declined to open a civil-rights investigation into the incident.

Aftermath and Judicial Intervention

In the days following the shooting, widespread protests erupted in Minneapolis and other U.S. cities. In response to legal challenges, federal judges issued rulings designed to curtail ICE’s tactics in protest settings. One injunction bars federal agents from detaining or using force—including tear gas or pepper spray—against peaceful protesters or bystanders who are not interfering with enforcement activities without reasonable suspicion of criminal activity, citing First and Fourth Amendment concerns. Despite these rulings, ICE leadership has indicated that its enforcement operations will continue largely unchanged.

Pattern and Constitutional Implications

The pattern is clear: when a civil enforcement agency uses criminal-style force under reduced procedural safeguards, constitutional protections can erode through routine practice rather than clear policy changes. What begins as immigration enforcement thus becomes a broader test of constitutional restraint—one that citizens increasingly encounter directly as federal operations extend beyond traditional immigration contexts.

Extraordinary Measures in Historical Context

ICE fits a documented historical pattern: security forces created in response to extraordinary threats tend to outlive the emergencies that justified them—and expand beyond their original purpose.

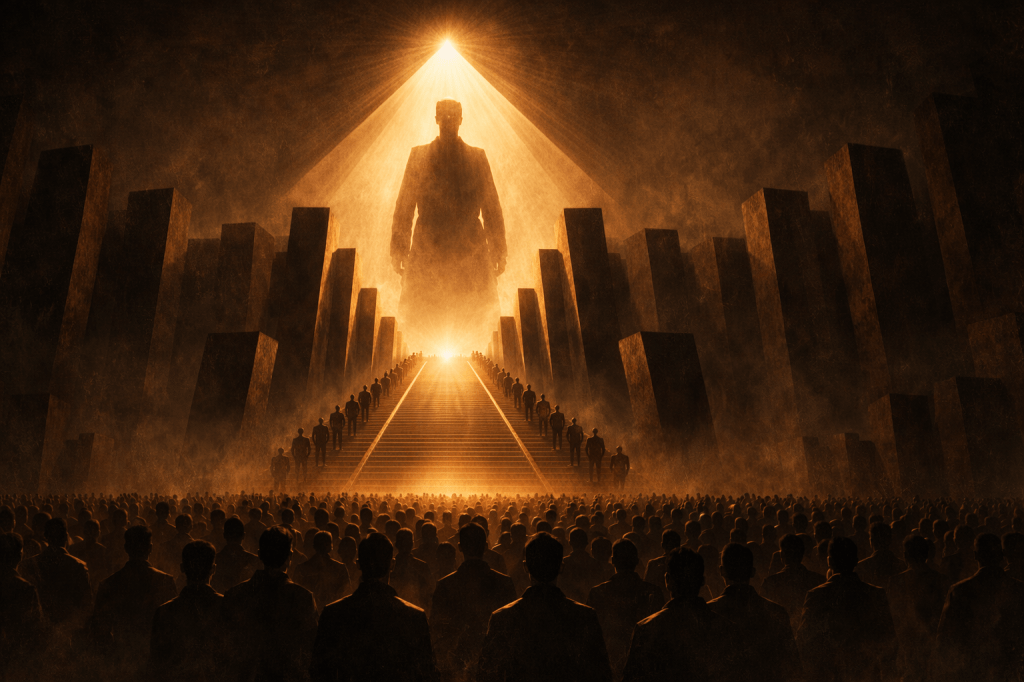

Emergency logic follows a recurring sequence:

- A grave threat is declared

- Ordinary law is deemed insufficient

- Extraordinary authority is granted

- Oversight weakens

- Emergency power becomes permanent

ICE was created at step three, in response to 9/11. Two decades later, the original threat has receded, but the powers have expanded in scope, been institutionalized, and are increasingly directed inward – step five?

Historical Parallels

Authoritarian regimes institutionalized this same logic through internal security forces that abandoned legal constraint. This is not saying ICE is equivalent in ideology, intent, or scale, yet..

The comparison matters for one reason only: the mechanism is familiar.

Democracies rarely lose liberty all at once. Instead:

- Extraordinary measures become normalized

- Oversight weakens under urgency

- Enforcement spreads into ordinary life

- Citizens—not only targeted groups—begin to feel the effects

A democracy can retain formal legality while operating under permanent emergency rules.

Rhetoric Weaponized

Rhetoric is one of the strongest tools used to justify extreme power. It starts by naming a threat and calling it a danger to everyone. Then it claims that normal rules no longer work. Repeated often enough, this story begins to sound like common sense—supported by small pieces of truth that make much bigger claims feel believable.

Historically Grounded Composite Quotations

Lightly paraphrased and presented without attribution to preserve meaning while exposing the structure and mechanics of emergency rhetoric, rather than amplifying its emotional charge.

On existential danger

“The nation stands at the edge of destruction.”

“We face a threat not to policy, but to survival itself.”

“If decisive action is not taken, there will soon be no country left to govern.”

“This is not a normal crisis—it is a struggle for existence.”

On internal enemies

“The danger comes from within, not from abroad.”

“These forces live among us, exploiting our freedoms to destroy us.”

“They are incompatible with the life of the nation.”

“One cannot coexist with those who work for national ruin.”

On the failure of ordinary law

“Normal law is too slow for the danger we face.”

“Legal restraints protect the enemies of the people.”

“Rules designed for peaceful times cannot meet an existential threat.”

“When survival is at stake, procedure becomes a luxury.”

On delegitimizing restraint

“Those who insist on legality are blind to reality.”

“Appeals to rights only strengthen those who would destroy us.”

“Order cannot be restored through debate.”

“Indecision is itself a form of betrayal.”

On extraordinary measures

“Exceptional threats require exceptional action.”

“Harsh measures are regrettable, but necessary.”

“Responsibility demands action beyond ordinary limits.”

“Authority must be concentrated if the nation is to be saved.”

On permanence

“This is not a temporary struggle.”

“The danger will return if vigilance weakens.”

“Security must become the foundation of governance.”

“The future requires strength, not hesitation.”

Why this matters

Individually, each claim can sound plausible in moments of fear. Taken together, they form a recognizable structure: existential threat, internal enemies, the delegitimation of law, and the normalization of extraordinary power.

Across 20th-century authoritarian regimes—most notably in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy—this rhetorical sequence was used to transform crisis into permanence, recasting emergency authority as necessity and restraint as betrayal. History shows that it is this structure, more than any single ideology, that enables emergency power to harden into enduring authoritarian rule.

Again, the claims are not inherently false in and of themselves.

They become dangerous when they are detached from time limits, proportionality, and oversight—when emergency framing hardens into permanent governance.

Emergency Framing in Contemporary American Politics

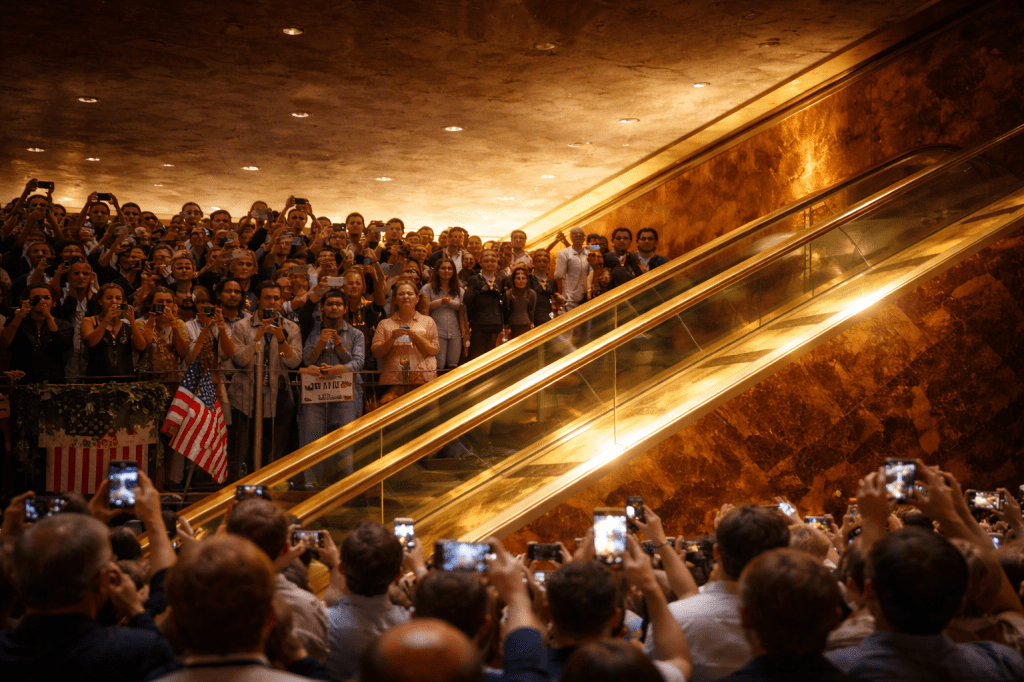

This emergency logic entered contemporary American politics explicitly in June 2015, when a candidate for the 2016 presidential election framed immigration not as a policy challenge, but as a threat to national survival.

The announcement speech opened by declaring crisis and institutional failure: “Our country is in serious trouble… We have no protection, and we have no competence.” Immigration was then described in broad, criminal terms: “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” The issue was tied directly to national existence itself: “We don’t have a country if we don’t have borders.”

This is a classic rhetorical move known as scapegoating: identifying a vulnerable group and assigning it responsibility for complex social and economic problems. In this case, immigrants—particularly Mexican immigrants—were cast as the source of national decline. Historically, similar logic has been used elsewhere to target Jews, communists, and other internal “enemies.”

Having established danger and collapse, the candidate presented extraordinary action as the only solution: “I will build a great wall… We need somebody that will take this country back.”

The importance of the speech lies less in any single line than in its structure. Immigration was recast as an existential threat, ordinary governance was portrayed as inadequate, and extraordinary enforcement was framed not as a policy choice, but as a necessity.

This is how crises are rhetorically constructed—not through a single decree, but through a narrative in which law appears insufficient and expanded power begins to feel inevitable long before it is formally enacted.

The Empirical Reality Behind the Rhetoric

At the time of the 2015 announcement, the empirical reality of immigration in the United States bore little resemblance to the crisis being described.

Immigrants made up roughly 13.5 percent of the U.S. population—a significant share, but not historically unusual. Most had lived in the country for years, often decades, and were deeply integrated into families, workplaces, and communities.

Crime data consistently contradicted the threat narrative. Research showed that immigrants—both documented and undocumented—were less likely to commit violent crime than native-born Americans, and that communities with higher immigrant populations often experienced lower crime rates. There was no evidence of an immigration-driven crime wave.

Economically, immigrants were working and contributing across the labor market, filling essential roles in construction, food production, caregiving, hospitality, manufacturing, and high-skill fields such as medicine, engineering, and technology. Millions paid taxes, supported local economies, and helped sustain labor-force growth in an aging society. Entrepreneurship followed the same pattern: immigrants were at least as likely as native-born Americans to start businesses and were overrepresented among founders of high-growth companies. Without immigration, U.S. economic growth, innovation, and global competitiveness would suffer.

None of this suggests immigration posed no challenges.

But it does reveal a stark gap between measured reality and existential framing.

The danger was not immigration itself.

It was the narrative.

By casting immigration as a collective criminal threat and a crisis of national survival—despite evidence of lower crime and broad economic contribution—emergency logic was activated. Once a phenomenon is defined as existential, ordinary law appears inadequate, and extraordinary measures begin to feel necessary.

The treatment of unlawful immigration as a problem requiring a permanent, militarized extraction force is a recent choice—not a historical necessity. The United States has addressed undocumented immigration through other approaches, often with less harm and greater stability.

Legalization and regularization.

The 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) legalized nearly three million undocumented immigrants already embedded in U.S. communities. The logic was pragmatic: people integrated into the workforce and families are more effectively governed inside the legal system than pursued outside it.

The result of IRCA, and the result was increased order, higher tax compliance, and social stability, not chaos or criminal collapse.

IRCA didn’t fail because legalization caused problems. It failed because the rest of the system stayed broken: employers weren’t seriously enforced, legal work visas didn’t match real labor needs, and there was no ongoing path to legal status. Without those pieces, new unauthorized immigration was almost inevitable.

Civil labor enforcement.

For much of U.S. history, enforcement focused on employers rather than workers—using labor inspections, fines, and compliance mechanisms instead of armed raids. This recognized that undocumented labor is largely demand-driven.

Administrative processing, not criminalization.

Immigration violations were historically treated as civil status matters, handled through notice, hearings, and supervised release rather than mass detention.

Targeted enforcement.

Even during enforcement-heavy periods, resources were often prioritized toward individuals convicted of serious violent crimes, rather than broad population sweeps that destabilize communities.

Structural and foreign-policy approaches.

Migration pressures were also addressed through diplomacy, development, and regional stability—treating migration as a structural phenomenon, not an invasion.

A Necessary Caveat

Presenting facts against fear-based rhetoric rarely changes minds. Fear does not arise from data, but it is seldom undone by it. Naming the gap still matters—not because facts alone persuade, but because unchecked narratives are how emergencies are manufactured, normalized, and sustained.

Bottom Line

The phrase “extraordinary threats require extraordinary measures” is not wrong.

It is incomplete.

It raises a deeper question: what are we being taught to fear—and why?

History shows that extraordinary measures rarely remain temporary. They become institutions, acquire momentum, and quietly reshape the boundary between state power and individual liberty.

ICE is not an aberration.

It is a case study in how emergency logic hardens into normal governance.

The danger is not that leaders name threats—but that once threats are declared existential, law becomes conditional and extraordinary power becomes routine.

Extraordinary threats demand extraordinary measures.

The question is: who decides what counts as a threat—what are you, what are we – afraid of?